A discussion of how the Internet will become the Information Superhighway.

When Thomas Edison invented the electric light bulb in 1879, it would have been hard to conceive that within the space of a lifetime, man would have sent a craft to the moon. Accompanying this period was the development of communications technology, whereby in the early 1960s, satellites allowed man to connect over the entire globe[1]. The result was a shift in political and social attitudes; the rise of feminism, a blurring of class boundaries and the spread of capitalist democracy[2]. The technological developments were so swift that many thought that by the year 2000, man would be indulging in space travel at will, have no shortage of food and would be able to treat all ills[3]. What happened instead was that after the Second World War, science became increasingly concerned with the development of ways to deal with information. The technological culmination of this today is the Internet, and predictions for the future (such as the Information Superhighway) are commonly based around advances of it.

The primary aim of this essay is to consider how the Internet will become the Information Superhighway. To do this, the issue of why the Internet is a unique communications technology needs to be understood, and then why it will become the Information Superhighway. The reason for this, I will argue, is bound in the reasons of why society adopts technology in any case. I will explore these issues in commercial, social and political terms. At the conclusion the reader should be in no doubt as to what the Information Superhighway is, how many influential pundits on this matter feel about it, and why it is genuinely important to consider.

STUDY OF THE INTERNET

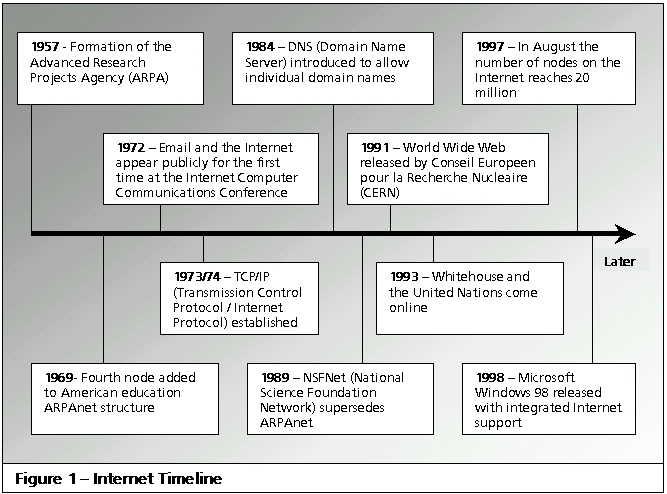

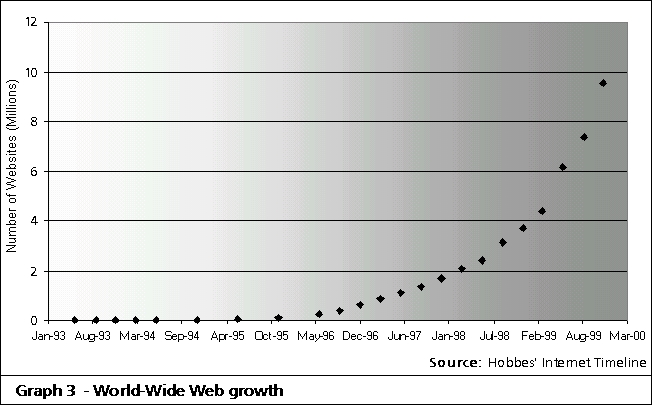

In spite of its dramatic growth in the 1990s[4], the origins of the Internet can be traced back to the formation of the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) in 1957, by the United States' Pentagon. The body's study led to the military ARPAnet, a network robust enough to survive a nuclear attack. In December 1969, the fourth node was added to an academic network in the United States, primarily as an educational tool on the ARPAnet structure. This event is the precursor to the modern day Internet. Originally, the Internet was supposed to be a tool for heightened production and wide-scale programming efforts. What it became was a communications tool for academics, separated by long distances, for discussion and information transfer[5].

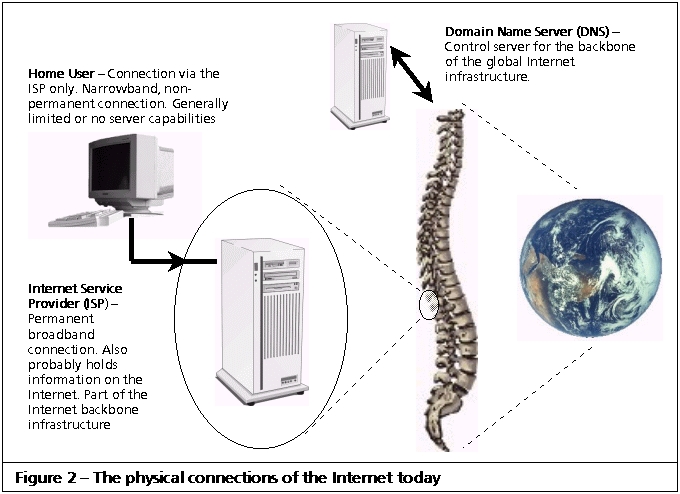

The pace of developing the Internet has been astounding. When the restrictions on commercial use of the Internet were relaxed in 1991, the infrastructure itself began to benefit from an influx of money[6]. The Internet and its infrastructure should be seen as two separate entities because, as it develops into the Information Superhighway, the most notable change will be to the infrastructure, not the Internet. The Internet is essentially the protocols (TCP/IP) which allow any computer to 'talk' to any other computer. These protocols can be adhered to by any system - from standard home Windows based computers to the most expensive super computers - and over any type of network - from the telephone system to cable based loops. Currently, most people access the Internet using telephone lines[7], with their connection therefore narrowband and limited by time. The terms broadband, narrowband and mid-band, refer to the bandwidth, or data transfer rate, of the connection being used. Broadband access is typically defined in the range of "1.2 to 6.0 million bits per second (which) is well suited for most existing multimedia"[8].

The Internet is distinct from the World Wide Web (WWW), which is a system whereby people can easily manoeuvre themselves around the Internet using browsing software. Although it is possible to use the Internet without the WWW, just as it is possible to use a computer through the user-unfriendly DOS environment, most people operate within the confines of a browser. The WWW has to conform to universal standards and so most browsers will be able to display the information presented in a useful form, even if the browser is an older version. Without the WWW, the Internet would not be accessible or useful to most people because a graphical, user-friendly interface[9] is essential in helping people adopt such complex technology.

THE INFORMATION SUPERHIGHWAY

To actually trace the roots of the term, 'Information Superhighway', is not difficult. In 1994, Al Gore introduced the term stating that the "Information Superhighway (will) allow us to share information, to connect, and to communicate as a global community.[10]" What is difficult, however, is to comprehensively define exactly what is meant by this term. The global telephone network certainly appeals to criteria Gore assigns to the Information Superhighway, however no one would mistake it for this. If the Internet is to evolve into the Information Superhighway, then the definition we have of it must be precise enough to allow us to comprehensively decide exactly when the transition occurs.

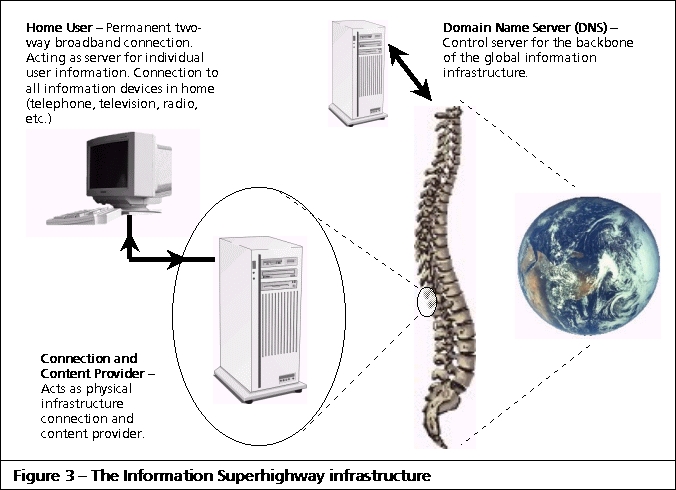

There are various factors which need to be examined to ascertain any suitable definition. The most notable are the technical aspects, because these are the physical connections which allow the network to exist in the first place. "The Information Superhighway ... is very much a physical network, an infrastructure of modern high-speed links which will connect homes and workplaces to each other.[11]" In this sense, it is practically identical to the Internet, with the expectations that the connections are broadband and continuously running. Access to the Information Superhighway will be more akin to current digital television access, rather than existing Internet access. The user pays to have access, which is always on, and then just selects when they want to use it. If any other user wants to view data put on the Information Superhighway, even if it is on another users' computer, they simply need call it up. Connection to the Information Superhighway must be able to support two way video communications as a minimum to be considered broadband enough, hence current solutions such as ADSL mid-band connections, do not constitute the Information Superhighway[12]. "ADSL isn't a full solution ... because it doesn't offer enough bandwidth to feed different programming to multiple TV sets in a house.[13]"

Other factors, which concern the Information Superhighway, are more abstract. Jonscher considers the Information Superhighway to be a metaphor for a communications network which allows transportation within its own particular space[14]. The space in question is what William Gibson referred to as 'Cyberspace', the "virtual realm"[15]. Movement or transmission in Cyberspace is accomplished electronically, hence the comparison with a highway is apt because it also exists solely to facilitate movement[16]. Negroponte's seminal classic, 'Being Digital' explores the distinction between flows of movement in the real world and the virtual realm in terms of atoms and bits[17]. Atoms are physical, and go to make up the physical objects we move about. Bits are information comprised of digital form, and these are what flow over the electronic links. Bits cannot distinguish the type of information they convey, hence any highway for transporting bits, is able to move any type of information through it.

Ultimately these factors provide a very specific definition which we can appeal to, in the pursuit of a path to the Information Superhighway. The Information Superhighway is a physical network, facilitating the broadband, two-way transmission of any type of digital information, within its own virtual space.

DIGITAL NETWORKS

Armed with a definition of the Information Superhighway what becomes clear is that, technologically, it is an evolution of the Internet. The physical nature of the Information Superhighway dictates that a communications infrastructure capable of supporting broadband connections will have to be established. The route to establishing such an infrastructure are commercial and political issues, which will be considered later, however it is first important to understand the technological benefits of having a digital infrastructure.

Digitisation

The major distinction between the traditional transmission of information and that of the Information Superhighway is that it will be digital. The term 'digitisation' refers to the translation of any typically analogue source into digital format. Examples of such translation are music to the CD (Compact Disc) format, television to DTV (digital television), and newspapers or magazines to hypertext (for viewing on the WWW). The transition from the Internet, which generally operates over the analogue telephone networks, to the Information Superhighway requires a shift towards a pervasive digital network. There are four key advantages to the transmission of information in digital form:

1. Integrity of the information

A digital signal is simply the code (1s and 0s), which represents the original analogue information. The quality transmission or replication will be maintained because it is the digital code which is being copied. If this is inaccurate, the entire process fails. With digital information, you can only have either a perfect copy or one that does not work at all.

2. Manipulation

Digital information can be manipulated with relative ease compared to analogue information. The most standard form that this takes is using a computer program to alter the information before it is outputted. Images taken on a digital camera, for instance, can be manipulated using a computer before they are printed to produce effects not captured when the picture was originally taken. The connotations of manipulating information are usually negative, however most digital information is manipulated. This might take the form of airbrushing red eye out of a photo or even adding the score to the moving images of a televised football game. Neither of these applications naturally occur, yet are valued positively.

3. Compression

Information translated to a digital code exists as very frequent approximations of the analogue source it seeks to represent. Digital music, for instance, is typically the collection of 44,000 approximations of the original analogue information each second. The human ear cannot distinguish between 44,000 approximations and so both digital and analogue pieces sound the same. Much of the information collected over 44,000 times in one second is the identical, hence with compression techniques redundant information can be removed. The upshot of this technique is that it takes less bandwidth to communicate information. This is why digital television has the capacity for more channels than standard analogue TV and why we can fit 10-15 times more music on a CD using digital compression than with standard techniques.

4. Convergence

All information in digital form is comprised of the same bits - 1s and 0s - be it music, image, text, video, or whatever, and so can be communicated using the same infrastructure. Any digital network allows the transmission of any type of information and as such represents "the convergence of the computer and telecommunications"[18]. Any device connected to the digital network will be able to collect any information on that network, although this is no guarantee that it will be able to process that information. A digital television set-top box with the capacity for email will be able to receive a computer data file, but that does not mean that it will be able to usefully process it in the same way that a PC might. Devices connected to the Information Superhighway, or indeed the Internet, only need to be able to adhere to the protocol of the transmission of information across that network. Hence, the concept of convergence ultimately relates to the flows of data rather than the capacity of devices for processing that information.

At this point in the essay we understand what the Information Superhighway is, where it came from and what the technological advantages of having the digital infrastructure are. The two essential questions asked at the beginning were why and how the Internet was going to become to the Information Superhighway. The answers lie in the applying the understanding of the technology to the concept of why any technology is adopted at all.

John Street and Raymond Williams discuss the arguments of technological determinism; that the most powerful influence on the development of society can be seen as an expression of technological development. "Progress ... is the history of ... inventions which 'created the modern world'"[19]. In its most basic form, this is the argument of technology for technology's sake. However, both acknowledge that this is not the only cause of technological innovation, citing social issues as factors also. Where Williams sees technological advancement predominantly determinist (either social or technological), Street perceives such views as "flawed to the extent that they overlook the combination of political, scientific and cultural processes that construct the technology.[20]" These processes should account for the idea that technology must add inherent value to our lives. As Bill Gates points out, technology can only reach commercial viability when people choose to adopt it, because "the marketplace is the greatest decision-maker.[21]" History dictates that technology which exists for its own sake is largely ignored or unsuccessful in mainstream consumption. We need only look at the public uptake of the VHS videotape format over the technologically superior Betamax format to show this. The success of VHS can be attributed to the application of the technology; there was a larger and better library of VHS tapes available.

Therefore, to understand how the Internet we currently have will become the Information Superhighway, it has to be shown that the Information Superhighway adds value to human life and that the development of the technology is commercially viable.

POLITICAL

Building the physical infrastructure for the global Information Superhighway highlights the fact that real space is dissimilar to cyberspace. Whilst the network itself is oblivious to the physical infrastructure which forms its links, geographical boundaries and financial considerations, those who will build it are not. A study of how communications infrastructures have developed in the United Kingdom, and how the development of digital networks is different, will help to explain the political considerations of building the Information Superhighway.

Traditionally where communications technologies have been concerned, political powers have always sought to regulate their use. After the First World War interrupted growth in the amateur use of radio and telegraphy, the government only allowed for public consumption through the regulation of the BBC in 1922. Television too has been heavily affected, as has telephony, with the government directly regulating these communications methods. However, the convergence of telecommunications and computing at the latter end of the twentieth century forced governments to realise that nationalised organisations could no longer match the pace of change in this field. Frederick Williams notes that one of the most likely physical infrastructures for the information society will be fibre optic cable, because of their broadband capacity[22]. As Negroponte states, "a fibre the size of a human hair can deliver every issue ever made of the Wall Street Journal in less that one second.[23]" In 1981, Margaret Thatcher's government passed the 'British Telecommunications Act', which was the start of government transferring control of the development of information infrastructures over to the commercial sector. The government held the belief that "market forces were better suited to cope with the rapidly changing requirements of the telecommunications field than a single monopoly network under rigid control.[24]"

Certain commentators, such as Ganley, feel that the reduction in state control of telecommunication is a desirable and natural consequence of the development of global information infrastructures. Advances in telecommunications not only empower individuals and their views, but allow them to be influenced from a greater variety of unmediated sources[25]. With digital networks existing as globalised entities, it would be an odd notion to suppose that they should be bound by the regulations of geographically confined establishments such as governments. Hence, through deregulation, the government has passed the risk and potential rewards onto the international commercial sectors, allowing them to write off the huge amounts of capital investment in old telephony systems, to create this "new generation of networks"[26].

COMMERCIAL

Bill Gates believes that deregulation of the communications industry is the key factor in the development of a successful Internet[27]. With this deregulation, "by the tenth anniversary of information highway mania, the Internet will deliver the full highway we envisioned.[28]" The development of the Information Superhighway, in an environment of deregulation, relies upon the commercial marketplace to establish the infrastructure. The commercial marketplace exists, primarily, to be commercially viable for those organisations which operate within it. Commercial viability is reliant to consumers or businesses willing to invest capital into the commercial organisation, either because of its product or services. Hence the transition from the Internet to the Information Superhighway is reliant upon both commercial / economic and consumer / cultural issues directly.

James Slevin considers these issues in relation to the theory of globalisation, which must be seen in both economic and cultural terms, when people or organisations seek to operate on a global stage. "We now live in a 'global society' in which we can no longer avoid other individuals or other ways of life.[29]" Manuel Castells, in his 'introduction to the information age', discusses how, "the information age is organised around new forms of time and space: timeless time, the space of flows.[30]" Both theorists are considering the same issue here, and the primary one in the commercial considerations of the growth in global information infrastructures, Cyberspace; the global space in which commercial organisations seek to operate. The 'virtual realm' consists of the 'new forms of time and space', but directly relates and interacts with real space. Financial institutions, for instance, move money around the world within this virtual realm. For the most part this money only exists electronically, yet still maintains proper value in the real world. Satellite television signals exist as nothing more than instantaneous transmissions. Nevertheless, millions around the world spend hours watching them. Cyberspace is not an alternative to the real world, but a method by which to bypass the space and time involved in moving information geographically.

Commercial organisations seek to operate within Cyberspace because they can target a global audience. Within this environment, geography and nationhood are largely irrelevant concepts, however they are still very prominent in the real world. Gates relates the story of how in a meeting with officials in Singapore, he asked if they realised that their policies on the deregulation of telecommunications would help reduce the strong control they held on information. They acknowledged that they did, but also realised the need to move with the times[31]. Chris Barker describes a similar position for Rupert Murdoch, where the real world issues forced him to take the "BBC from his Asian satellite system Star TV, apparently because BBC news was irksome to the Chinese government.[32]" The distinction between the two incidents was that Gates was discussing a globalised information infrastructure, whereas Murdoch was operating a media specific, geographically centric system.

One might have ascribed the differences between the positions Murdoch and Gates found themselves in, to their different industries. In the Internet age, this would be a valid point, but not in the age of the Information Superhighway. The Information Superhighway facilitates the convergence of content and distributions channels, which brings corporations such as Microsoft and News Corporation closer together, indicating huge commercial and cultural developments from the Internet.

Gates firmly holds the belief that video-on-demand will be the 'killer application', the essential technology that convinces consumers to adopt, for a broadband infrastructure[33]. Any user would be able to visit the website of a television channel and choose what to watch, at the time they wanted to watch it. It might not be presented as visiting a website, but the concept of the user interacting with their viewing schedule is the key component. The broadband Information Superhighway would facilitate such a service, because it would have the bandwidth available to stream video (to transmit video in direct response to the controls of the user). Moreover, the video would then be available to anyone with access to the Information Superhighway, globally. If the Chinese government were to accept the Information Superhighway into their country, they would have no power to influence the material their citizens wanted to watch.

Murdoch has realised this. In February 2000, Sky television unveiled their Internet strategy, expressing that, "in the future, Sky will sit happily whether it is on the PC, the mobile or on the television"[34]. If Sky can market their content globally, then they face the potential of a global market of users on the Information Superhighway. A more potent example of content and distribution convergence was seen a month earlier when AOL took over Time Warner in a bid at "revolutionising the way news, entertainment and the Internet are delivered to the home.[35]" Whilst AOL provides connection to the Internet, and a variety of content, the value of Time Warner came not only from the impressive content and brand name it had established, but also from its television subscriber base of over 100 million users in the United States alone[36]. AOL had bought content, distribution and a ready-made cable and satellite infrastructure.

In the commercial marketplace, the Internet, it seems, will naturally develop into the Information Superhighway because of the commercial opportunities it presents. Not only will organisations have the chance to appeal to a global market, but can also own the infrastructure itself, supported by the content which is viewed on it.

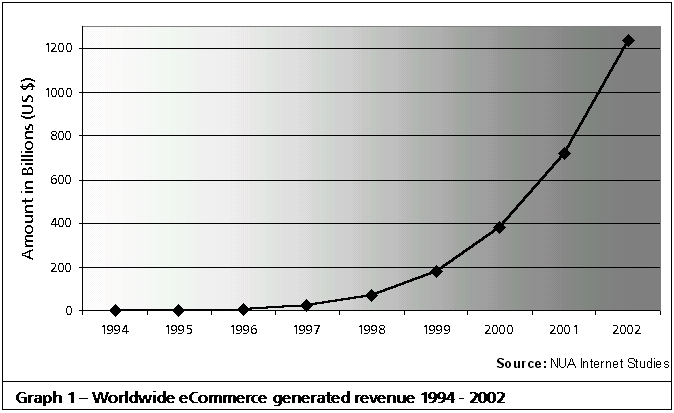

Further commercial opportunities are already being exploited in the form of electronic commerce (eCommerce), where companies utilise the digital network as a medium by which to present their products or merchandise to anyone with access. ECommerce over the Internet is a rising trend[37], which will continue to grow as the network reaches more people. However, because the development of the Information Superhighway is primarily an issue of physical infrastructure, it is not directly affected by eCommerce, which is a means of electronic distribution (either of information or sales presence). ECommerce content does not directly support the growth of the Information Superhighway, because it is not commercially related to the infrastructure which supports it (unlike those concerned with the issues of content distribution as discussed above). As noted the Information Superhighway will only develop if there is value for people in using it, and eCommerce is another factor which adds value. Hence, whilst eCommerce does not relate to the building of the infrastructure, it provides a compelling argument that there is some reason for consumers to adopt, for otherwise eCommerce figures over the Internet would not be increasing so dramatically.

CONSUMER

The immediate future of Information Superhighway is directly related to consumer uptake of the Internet, because the commercial model dictates that without this route, it will not be commercially viable to build a high bandwidth infrastructure. Whilst traditionally the Internet is usually seen as a feature of PCs, the most likely area of Internet access growth will be through the television. In 1998, over 97% of the population in the United Kingdom owned a television, and as digital television becomes the norm, the same penetration figure is likely to be applied to Internet access[38]. Forrester Research are predicting that by 2005 more people will be accessing the Internet through their televisions than through PCs, which will amount to over 80 million people in Europe[39]. These predictions may not be too ambitious because all those who subscribe to digital television services will have Internet access as standard. Cable & Wireless have announced their plans for Internet access for all digital television subscribers before the end of 2000, with no need for additional hardware[40]. ONdigital plan to bring "the Internet to everyone through their TVs, which are already in virtually every home in the country.[41]" To compound this, the government in the United Kingdom are seeking to be able to 'switch-off' analogue television before 2010[42]. Furthermore, there is the expectation that many other home devices will allow Internet access, such as videogame consoles (Dreamcast and PlayStation 2) or email-equipped telephones.

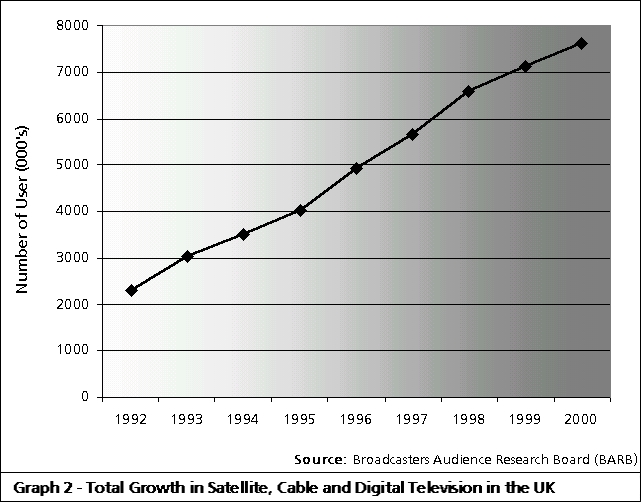

It is difficult to sustain a debate which supposes that Internet access will not become as pervasive as television (at least in the United Kingdom), because both government and commerce are interested in making this vision a reality. However, as previously noted, for technology to be successful, consumers must be willing to adopt in numbers. Without the benefits of online interactive digital television services, subscriber television services have already reached around a third of the penetration levels of traditional television, as is shown in the graph below. This alone is not enough to create the level of demand those, such as Forrester, are predicting. There has to be both a perceived and real benefit from increased levels of Internet access for consumers to fully invest in the technology that will bring about the Information Superhighway.

The benefits come from the changes in the distribution models of media, information, communications and products. The distinction, discussed earlier, Negroponte makes between atoms and bits explains the shift, where possible, from real world distribution, to distribution through Cyberspace. "The methodical movement of recorded music as pieces of plastic, like the slow human handling of most information in the form of books, magazines, newspapers, and videocassettes, is about to become the instantaneous and inexpensive transfer of electronic data that move at the speed of light.[43]" Negroponte sees little reason to manufacture information, when it can be cheaply and swiftly reproduced and distributed digitally.

Barwise and Hammond predict how the consumer world might be if there is such a shift in the distribution of information. In their world any data, from movies to text, can be instantly requested through an intelligent computerised agent[44]. As long as there is some access to the network (which in their prediction certainly qualifies as the Information Superhighway), then people can access their 'online' lives. Barwise and Hammond envisage that access will be practically everywhere, from cars to offices. Bill Gates foresees the use of wallet PCs, whereby full connectivity in the future will be a standard[45]. The wallet will act as a cellular telephone, monetary transfer device, digital authentication and link to the Information Superhighway. The prototypes of such devices are being seen in the form of the Third Generation (3G) mobile phone devices, which incorporate data connectivity, as shown in the figure below.

The possible developments suggested above all maintain the common philosophy that the Internet will become seamlessly integrated into the everyday lives of consumers. As such, there will be an increased need for bandwidth, to accommodate this integration, and the Information Superhighway will develop. There is the presumption that consumers will adopt because the technology "is not about computers anymore, it is about living"[46]. The convergence of media genres so that all information flows to and from along the same information highway does suggest seamless integration. Phillip Agre, however, argues that "this kind of monolithic story is wrong ... and particularly unfortunate when it comes to the future communications media (which) ... will continue to multiply.[47]" There should be a question raised over the idea that the traditional distinction of media types will perish so easily.

The question raised is over the ability to cause a shift in consumers attitudes to accept the technology. Technologically, television did not particularly develop between the introduction of colour in 1967 and the emergence of digital in 1998. The future of the Internet is heavily reliant on digital television, therefore by this rationale, there is no reason to presume a change is due for at least another 30 years. Consumers are not as inclined to change their television sets as often as they do their computing equipment. The result of this would be that consumers adopt the Internet as a standard feature of upgrading to digital television, but would not support the development of an infrastructure to support the Information Superhighway. Agre's position would be validated if this happened, because the Internet is too narrowband to support Negroponte's shifts in the distribution of information. Music would continue to be distributed as plastic CDs, the news would still be printed and users would still have to watch what is on the television rather than actively choosing.

This is the position of technological stagnation, whereby consumers are only willing to adopt the technology to a specific point. To further develop the Information Superhighway from this position requires those who believe in its potential to cause a shift in consumer attitudes towards this stance. The next section deals directly with this issue, and how society will develop with the view that there is enough value in the Information Superhighway to invest in its development from the Internet.

EDUCATION

Negroponte, Gates, Barwise, Hammond, and the other evangelists may well be ready for the information society, but this does not show that everybody else is. To assert that there is an information society is to express that information has become so important that it defines the age which we live in[48]. It is important to note, that the assertion that there is or will be an Information Superhighway, does not directly relate to the issue of whether or not there is an information society. The Information Superhighway presupposes growth in the importance of a digital information infrastructure to society, yet can bear no direct relationship to the method of quantifying whether or not the information society exists. The point where this growth in importance reached the mainstream occurred when the Internet began to appeal to the mainstream. "I can't tell you exactly when this point-of-no-return was reached, but by late 1995 we had crossed the threshold. More users meant more content and more content meant more users.[49]" The more value placed in Cyberspace, the more value is invested in building the infrastructure of the Information Superhighway. It is this simple equation that explains why there is commercial viability in extending the Internet. Only with a consumer market educated to the value of the Information Superhighway, will there be commercial viability in developing it.

Developed societies can be viewed in terms of two broad categories which need educating in the value of ICT (information communications technologies - the Internet, the Information Superhighway and any type of digital communications network). These are, young people, and those who have already grown up with analogue communications technologies.

Gates and Negroponte argue how bringing ICTs into the classroom will develop a fundamental understanding and appreciation of digital networks and tools. Gates especially sees education to be fundamentally lacking in resources towards this end, but feels this is a futile position because computers and networks could bring down the cost of education overall. "If we want better education - faster learning and better understanding - we have to find ways to get greater results for every dollar we spend.[50]" Negroponte concurs, noting how the opportunities through computing aspects such as multimedia and video-gaming foster essential skills in youngsters more easily than traditional methods. "Most adults fail to see how children learn with electronic games. ... There is no question that many electronic games teach kids strategies and demand planning skills that they will use later in life.[51]" Not only do both feel that education in this way is viable and essential, but their views are supported in the United Kingdom by the government, who have openly expressed the desire to increase Internet penetration levels in the school system[52]. The important placed on education with these tools will no doubt foster a latent value for digital networks in future generations.

The greater problem than instilling these values in children, is making them appeal to people who have not grown up with digital technologies. Consumers can be encouraged to invest through advertising and subsidising the technology (as has been done with digital television), however commentators such as Peter Cochrane and Michael Gell have noted how the issues of globalisation and increases in technology in the workplace are causing some to seek re-education anyway. People in the workplace, or at university level, become aware that they will need technological skills to successfully progress in their vocations. A direct consequence is a need for continuous learning to keep up with the technology[53], for which ICTs are the perfect educational tool. This provides the opportunity to use digital networks to offer people in the workplace and at university with access to an educational environment not bound by geography or indeed class sizes. "National boundaries will be increasingly bypassed as universities and companies provide education and training direct to customers through global networks.[54]" This is the perfect environment for Pierre Levy's 'campus of knowledge', whereby ICTs allow those who wish to be educated, access to the best minds the planet has to offer[55]. Gell and Cochrane cite examples where this type of learning has already begun. In 1994 the Open University offered its first course over the Internet, and in 1995 Stanford University followed suite[56]. The value placed in digital networks is a direct result of technology in the workplace, because people will actively seek continuous education as a natural part of their lives, which is well fulfilled by the Information Superhighway.

Noam Chomsky suggests that through such globalisation, society is "imposing the right priorities on a recalcitrant world.[57]" The march of technological innovation and adoption forces people into the route of continuous education in a bid to keep up. Effectively, the Information Superhighway will be built out of the Internet, because this is the 'right' development for society. Robins and Webster believe that, as such, technological development is essentially hegemonic towards the good, because without it society would either stand still or worse, degenerate towards Luddite values[58]. However there is a further view which argues that technological development, especially in the case of a global network, simply increases the disproportionate spread of technology on a global scale.

GLOBAL INFRASTRUCTURE?

Globalisation will not rid us of the inequality which exists between developed and third world nations, because they do not have an advanced enough communications infrastructure to embrace the global economy in which developed nations act[59]. The distinction is defined by Thussu as being between the developed countries and the "information starved", relating the concept of development to the issue of a shift in society towards information[60]. For many the Information Superhighway is a global development, a chance to achieve Marshall McLuhan's vision of the 'global village'[61], what has been termed the GII (global information infrastructure). However if the Information Superhighway is the result of a direct commercial development of the Internet, then "it will very likely enhance the communication inequality between, as well as within, nations.[62]" For Steven Miller, the GII is the same as the Information Superhighway[63], but this is too great an assumption. The definition of the Information Superhighway expressed earlier does not suggest that it needs to be fully pervasive network, but only one capable of being so. What this essay has expressed is the need for the Information Superhighway to provide real benefit to achieve adoption, and to therefore to be a development for the good. If the Information Superhighway ultimately causes even greater geographic inequality[64], then this is not an infrastructure capable of globalised benefit. Cyberspace need not be accessible to all, but it must present a real benefit for all who use it.

For many developing countries, or for countries who are economically disparate from the West, the Information Superhighway does offer something. Thussu, Miller, Allen and Hamnet all believe that the 'information revolution' will introduce new possibilities for economic growth and technological infiltration to the 'information starved'. In 1993, Indian software exports grew by around 47%, showing how cheaper labour can allow these countries to offer real competition and the opportunity to adopt these technologies as prime industries for economic development[65]. Thussu notes how the South-East Asian 'Tiger' economies have been built on the back of growth in technology markets[66].

The Information Superhighway fulfils the criteria of being a development for the good. Having explored the commercial benefits and consumer uptake in developed countries, such as the United Kingdom, there is reason to believe in the progression of the global digital network (currently the Internet), even towards countries to whom it might not be accessible presently. In spite of the use of the term, 'globalisation', the Information Superhighway does not have to fulfil the criteria of being globally available. Rather it creates a virtual space in which geography is inconsequential, Cyberspace. To argue in terms of geography, even when there is a physical infrastructure to consider, misses the point. Cyberspace will mature from the Internet to the Information Superhighway if there is real benefit for those who have the ability to access it, because the value they perceive in it will necessitate the physical infrastructure.

CONCLUSION

Underlying the question of how society might adopt the Information Superhighway, there is the issue of why it might want to at all. To develop a broadband infrastructure from the Internet is a huge undertaking, even in spite of the fact that its importance has increased through astonishing levels of growth. Whilst clearly there is technological merit from an advance in this direction, the Information Superhighway will only transpire in an environment in which there has been a cultivation of a shift in human attitudes towards it. To this end, the responsibility for the ICT evolution has been transferred from the political, regulatory arena, to the dynamic, globalised commercial sphere; which necessarily needs to appeal to the consumer markets to invest in the transition to the Information Superhighway. Although these markets suffer from global inequality, nonetheless adoption relies entirely upon the concept of value. This core tenet is the only universal that will make the development of the Information Superhighway a reality. "The computer and telecommunications industries ... lay bare a huge seam of public interest in a retooling of industrial society whose viability depended upon a mass preparedness to participate.[67]"

The dramatic growth of the Internet suggests that there is enough 'mass preparedness to participate' in digital networks, and so possibly the advancement on to the Information Superhighway. Whilst governments and commercial organisations can cultivate an environment of change, ultimately consumers will make the decision about a global broadband network. "One thing is clear: We don't have the option of turning away from the future. No one gets to vote on whether technology is going to change our lives. No one can stop productive change in the long run because the market place inexorably embraces it.[68]" To this point Gates has played a major part in shaping the information technology market, and whilst his foresight has been at times questionable - he famously managed to spot the potential of the Internet late[69] - it is too difficult to ignore his vision for the road ahead. There is every chance that the many evangelistic predications about the Information Superhighway will come to pass.

Notes

- p17, Lax, Stephen, Beyond The Horizon, (Luton : University of Luton Press, 1997)

- p167, Ganley, G., The Exploding Political Power of Personal Media (Norwood, New Jersey : Ablex Publishing Corporation, 1992)

- pp3-4, Jonscher, Charles, Wiredlife (London / Sydney : Anchor, 2000)

- See Graph 3 - 'Growth in WWW'

- p25, World Tourism Organisation, Marketing Tourism Destinations Online (Madrid: WTO, 1999)

- Hobbes' Internet Timeline (for URL, see World-Wide Web Addresses)

- Georgia Institute of Technology, GVU's WWW Survey (for URL, see World-Wide Web Addresses)

- p27, Negroponte, Nicholas, Being Digital (New York : Knopf, 1995)

- p38, Slevin, James, The Internet and Society (Cambridge / Malden, MA : Polity Press, 2000)

- p4, Gore, Al, 'Forging a new Athenian age of Democracy', Intermedia, 1994, vol. 27, no. 2

- p163, Jonscher, Charles, Wiredlife (London / Sydney : Anchor, 2000)

- ADSL (Asymmetric Digital Subscriber Line), a mid-band connection running between 0.5 and 2 Mbps. British Telecom ADSL (for URL, see World-Wide Web Addresses)

- p265, Gates, Bill, The Road Ahead (Revised Edition) (New York / London : Penguin Books, 1996)

- p65, Jonscher, Charles, Wiredlife (London / Sydney : Anchor, 2000)

- p188, Poster, Mark, 'Virtual ethnicity: Tribal identity in an age of global communications' in Jones, Steven (ed.), Cybersociety 2.0 (London / California : Sage Publications, 1998)

- p3, Jones, Steven (ed.), Virtual Culture (London / California : Sage Publications, 1997)

- Chapter 1, 'The DNA of Information', Negroponte, Nicholas, Being Digital (New York : Knopf, 1995)

- p81, Smith, Anthony, Books To Bytes: Knowledge& Information in the Postmodern Era (London : BFI Publishing, 1993)

- p46, Williams, Raymond (1974), 'The technology and the society' in MacKay, Hugh, & O'Sullivan, Tim (ed.), The Media Reader: Continuity and Transformation (London / New Delhi : Sage Publications, 1999)

- p391, Street, John (1997), 'Remote control? Politics, technology and 'electronic democracy' in MacKay, Hugh, & O'Sullivan, Tim (ed.), The Media Reader: Continuity and Transformation (London / New Delhi : Sage Publications, 1999)

- p282, Gates, Bill, The Road Ahead (Revised Edition) (New York / London : Penguin Books, 1996)

- p46, Williams, Frederick, The Communications Revolution (Beverley Hills/ London : Sage Publications, 1982)

- p23, Negroponte, Nicholas, Being Digital (New York : Knopf, 1995)

- p53, Hollins, T, Beyond Broadcasting: Into the Cable Age (London : BFI Publishing, 1984)

- p10, Ganley, G., The Exploding Political Power of Personal Media (Norwood / New Jersey : Ablex Publishing Corporation, 1992)

- p86, Smith, Anthony, Books To Bytes: Knowledge& Information in the Postmodern Era (London : BFI Publishing, 1993)

- p281, Gates, Bill, The Road Ahead (Revised Edition) (New York / London : Penguin Books, 1996)

- p317, Ibid.

- p200, Slevin, James, The Internet and Society (Cambridge / Malden, MA : Polity Press, 2000)

- p405, Castells, Manuel (1996), 'An introduction to the information age' in MacKay, Hugh, & O'Sullivan, Tim (ed.), The Media Reader: Continuity and Transformation (London / New Delhi : Sage Publications, 1999)

- p270, Gates, Bill, The Road Ahead (Revised Edition) (New York / London : Penguin Books, 1996)

- p44, Barker, Chris, Television, Globalisation and Cultural Identities (Buckingham / Oxford : Open University Press, 1999)

- p74, Gates, Bill, The Road Ahead (Revised Edition) (New York / London : Penguin Books, 1996)

- Harding, James, & Larsen, Peter, 'BSKYB unveils internet strategy', Financial Times, 10 February 2000

- Hill, Andrew, & Waters, Richard, 'Media titans in $327bn merger', Financial Times, 11 January 2000

- Waters, Richard, 'A new media world', Financial Times, 11 January 2000

- See Graph 1 - 'Worldwide eCommerce generated revenue 1994 - 2002'

- Broadcasters Audience Research Board (BARB) (for URL, see World-Wide Web Addresses)

- Forrester Research (for URL, see World-Wide Web Addresses)

- Cable & Wireless Telecommunications (for URL, see World-Wide Web Addresses)

- ONdigital (for URL, see World-Wide Web Addresses)

- Information Age Government Champions (for URL, see World-Wide Web Addresses)

- p4, Negroponte, Nicholas, Being Digital (New York : Knopf, 1995)

- p16, Barwise, Patrick, & Hammond, Kathy, Predictions: Media (London : Phoenix, 1998)

- p81-5, Gates, Bill, The Road Ahead (Revised Edition) (New York / London : Penguin Books, 1996)

- p6, Negroponte, Nicholas, Being Digital (New York : Knopf, 1995)

- p70, Agre, Philip, 'Designing genres for new media: social, economic, and political contexts', in Jones, Steven (ed.), Cybersociety 2.0 (London / California : Sage Publications, 1998)

- p138, Webster, Frank (1994), 'What information society?', in MacKay, Hugh, & O'Sullivan, Tim (ed.), The Media Reader: Continuity and Transformation (London / New Delhi : Sage Publications, 1999)

- p xi, Gates, Bill, The Road Ahead (Revised Edition) (New York / London : Penguin Books, 1996)

- p214, Ibid.

- p204, Negroponte, Nicholas, Being Digital (New York : Knopf, 1995)

- p5, Our Information Age - The Government's Vision, 1998

- pp252-3, Cochrane, Peter, & Gell, Michael, 'Learning and education in an information society' in Dutton, William, Information and Communication Technologies: Visions and Realities (Oxford : Oxford University Press, 1996)

- pp261-2, Ibid.

- p197, Levy, Pierre, Collective Intelligence : Mankind's Emerging World in Cyberspace, quoted in Robins, Kevin, & Webster, Frank, Times of the Technoculture (London / New York : Routledge, 1999)

- p258, Cochrane, Peter, & Gell, Michael, 'Learning and education in an information society' in Dutton, William, Information and Communication Technologies: Visions and Realities (Oxford : Oxford University Press, 1996)

- p6, Chomsky, Noam, 'Power in the global arena', in New Left Review, 1998, no. 230

- p51, Robins, Kevin, & Webster, Frank, Time of the Technoculture (London / New York : Routledge, 1999)

- pp36 - 59, Allen, J., & Hamnet, C., A Shrinking World? (Oxford : Open University Press, 1995)

- p64, Thussu, Daya, Electronic Empires: Global Media and Local Resistance (London / New York : Arnold, 1998)

- pp75-6, Martin, James, The Wired Society (Englewood Cliffs : Prentice Hall, 1978)

- p133, Herman, Edward, & McChesney, Robert (ed.), The Global Media: The New Missionaries of Corporate Capitalism (London : Cassell, 1997)

- p346, Miller, Steven, Civilizing Cyberspace (New York : ACM Press, 1996)

- The notion here expressly means that the information society must not cause increased hardship globally, as opposed to the alternative reading that it might encourage inequality between developed and underdeveloped countries to grow.

- p346, Miller, Steven, Civilizing Cyberspace (New York : ACM Press, 1996)

- p65, Thussu, Daya, Electronic Empires: Global Media and Local Resistance (London / New York : Arnold, 1998)

- p88, Smith, Anthony, Books To Bytes: Knowledge& Information in the Postmodern Era (London : BFI Publishing, 1993)

- p11, Gates, Bill, The Road Ahead (Revised Edition) (New York / London : Penguin Books, 1996)

- p157, Jonscher, Charles, Wiredlife (London / Sydney : Anchor, 2000)

Bibliography

-

Agre, Philip, 'Designing genres for new media: social, economic, and political contexts', in Jones, Steven (ed.), Cybersociety 2.0 (London / California : Sage Publications, 1998)

- Allen, J., & Hamnet, C., A Shrinking World? (Oxford : Open University Press, 1995)

- Barker, Chris, Television, Globalisation and Cultural Identities (Buckingham / Oxford : Open University Press, 1999)

- Barwise, Patrick, & Hammond, Kathy, Predictions: Media (London : Phoenix, 1998)

- Castells, Manuel, The Rise of Network Society (Oxford / Malden MA : Blackwell, 1996)

- Castells, Manuel (1996), 'An introduction to the information age' in MacKay, Hugh, & O'Sullivan, Tim (ed.), The Media Reader: Continuity and Transformation (London / New Delhi : Sage Publications, 1999)

- Chomsky, Noam, 'Power in the global arena', in New Left Review, 1998, no. 230

- Cochrane, Peter, & Gell, Michael, 'Learning and education in an information society' in Dutton, William, Information and Communication Technologies: Visions and Realities (Oxford : Oxford University Press, 1996)

- Dutton, William, Information and Communication Technologies: Visions and Realities (Oxford : Oxford University Press, 1996)

- Ganley, G., The Exploding Political Power of Personal Media (Norwood / New Jersey : Ablex Publishing Corporation, 1992)

- Gore, Al, 'Forging a new Athenian age of Democracy', Intermedia, 1994, vol. 27, no. 2

- Gates, Bill, The Road Ahead (Revised Edition) (New York / London : Penguin Books, 1996)

- Harding, James, & Larsen, Peter, 'BSKYB unveils internet strategy', Financial Times, 10 February 2000

- Herman, Edward, & McChesney, Robert (ed.), The Global Media: The New Missionaries of Corporate Capitalism (London : Cassell, 1997)

- Hill, Andrew, & Waters, Richard, 'Media titans in $327bn merger', Financial Times, 11 January 2000

-

Hollins, T, Beyond Broadcasting: Into the Cable Age (London : BFI Publishing, 1984)

- Jones, Steven (ed.), Virtual Culture (London / California : Sage Publications, 1997)

- Jones, Steven (ed.), Cybersociety 2.0 (London / California : Sage Publications, 1998)

- Jonscher, Charles, Wiredlife (London / Sydney : Anchor, 2000)

- Lax, Stephen, Beyond The Horizon (Luton : University of Luton Press, 1997)

- Levy, Pierre, Collective Intelligence : Mankind's Emerging World in Cyberspace, quoted in Robins, Kevin, & Webster, Frank, Times of the Technoculture (London / New York : Routledge, 1999)

- MacKay, Hugh, & O'Sullivan, Tim (ed.), The Media Reader: Continuity and Transformation (London / New Delhi : Sage Publications, 1999)

- Martin, James, The Wired Society (Englewood Cliffs : Prentice Hall, 1978)

- Miller, Steven, Civilizing Cyberspace (New York : ACM Press, 1996)

- Negroponte, Nicholas, Being Digital (New York : Knopf, 1995)

- Our Information Age - The Government's Vision, 1998

- Poster, Mark, 'Virtual ethnicity: Tribal identity in an age of global communications' in Jones, Steven (ed.), Cybersociety 2.0 (London / California : Sage Publications, 1998)

- Robins, Kevin, & Webster, Frank, Times of the Technoculture (London / New York : Routledge, 1999)

- Slevin, James, The Internet and Society (Cambridge / Malden, MA : Polity Press, 2000)

- Smith, Anthony, Books To Bytes: Knowledge& Information in the Postmodern Era (London : BFI Publishing, 1993)

- Steemers, Jeanette (1997), 'Broadcasting is dead. Long live digital choice.' in MacKay, Hugh, & O'Sullivan, Tim (ed.), The Media Reader: Continuity and Transformation (London / New Delhi : Sage Publications, 1999)

-

Street, John (1997), 'Remote control? Politics, technology and 'electronic democracy' in MacKay, Hugh, & O'Sullivan, Tim (ed.), The Media Reader: Continuity and Transformation (London / New Delhi : Sage Publications, 1999)

- Thussu, Daya, Electronic Empires: Global Media and Local Resistance (London / New York : Arnold, 1998)

-

Waters, Richard, 'A new media world', Financial Times, 11 January 2000

- Webster, Frank (1994), 'What information society?', in MacKay, Hugh, & O'Sullivan, Tim (ed.), The Media Reader: Continuity and Transformation (London / New Delhi : Sage Publications, 1999)

- Williams, Frederick, The Communications Revolution (Beverley Hills/ London : Sage Publications, 1982)

- Williams, Raymond (1974), 'The technology and the society' in MacKay, Hugh, & O'Sullivan, Tim (ed.), The Media Reader: Continuity and Transformation (London / New Delhi : Sage Publications, 1999)

- World Tourism Organisation, Marketing Tourism Destinations Online (Madrid: WTO, 1999)

World-Wide Web Addresses

- British Telecom

ADSL

http://www.bt.com/adsl

Viewed: 13th April 2000

- Broadcasters Audience Research Board (BARB)

- Cable & Wireless Telecommunications

http://www.barb.co.uk/tvfacts/story.cfm?ID=41

Viewed: 16th April 2000

- Forrester Research

http://home.cwcom.net/public/o_products/tv/digitaltv/digital2.htm

Viewed: 16th April 2000

- Georgia Institute of Technology, GVU's WWW Survey

http://www.forrester.com/ER/Press/Release/0,1769,259,FF.html

Viewed: 16th April 2000

- Hobbes' Internet Timeline

http://www.gvu.gatech.edu/user_surveys/survey-1998-10/graphs/technology/q01.htm

Viewed: 11th April 2000

- Information Age Government Champions

http://www.isoc.org/zakon/internet/History/HIT.html

Viewed: 12th April 2000

- NUA Internet Studies

http://www.iagchampions.gov.uk/guidelines/digitaltv/services.html

Viewed: 16th April 2000

- ONdigital

http://www.nua.ie/surveys

Viewed: 12th April 2000

http://www.ondigital.co.uk/behind_press_home.html#press67

Viewed: 16th April 2000